Aim

To consider, in present-day Nigeria or even in the near future, the possibility of Nigerian health workers working synergistically instead of antagonistically to achieve quality service delivery against present practices where one arm of the healthcare delivery system seeks to lord it over the rest of the arms.

Given

Utopia, Nigeria, Medical Laboratory Scientists, Doctors, Nurses, Health Professionals, Collaboration, Healthcare Delivery System.

Method

An exploratory essay

Principle

Utopia, noun

Pronunciation: /juˈtəʊpɪə/ or yoo-TOH-pee-ə

Meaning

An idealised place or state, especially a society, with perfect conditions and laws.

From Ūtopia, the name of a fictional island possessing a seemingly perfect socio-politico-legal system in the book Utopia (1516) by Sir Thomas More. More derived this word from two Greek words, ou (no, not) + topos (place).

Example Sentence

Utopia is when a Nigerian hospital has water, electricity, and unity among its health workers—all on the same day.

Implied meaning usage

In a perfect world [Utopia], we [healthcare workers] will only have the utmost concern for our customers [the patients] instead of silly notions like ego and who should lead the system.

Antonym

Dystopia

Healthcare delivery in Nigeria has evolved. With the increase in complex health needs due to an ever-expanding population and changes in living conditions, healthcare service delivery should have improved significantly. But what we have presently is a far deviation from our idealistic dream, as we are underperforming compared to our regional peers.

Indeed, we have gone from curative therapies delivered primarily by physicians and nurses during the colonial period to what we have now, where there are diverse healthcare workers—laboratory scientists, nurses, community health workers, radiographers, and physiotherapists—who have distinct fields unified under the umbrella of patient care. This diversification of healthcare professions was needed to improve service delivery across various levels of care. However, it also introduced new challenges, particularly in interprofessional collaboration and role clarity. Today, healthcare in Nigeria is delivered by a mosaic of professionals, each contributing uniquely but not always cohesively.

Against this backdrop, the concept of utopia—an ideal state where all healthcare workers function collaboratively, harmoniously, and efficiently—raises an important question: Is such a reality attainable in Nigeria’s current system, or is it an aspirational vision constrained by systemic, cultural, and structural barriers?

Where [in a utopian world] we expect seamless communication among healthcare professionals, why do we still palpably see power tussles? This essay explores the tensions and barriers that currently hinder synergy among healthcare workers and whether the idea of utopia is a pipe dream or a goal worth pursuing.

Procedure

Where we are: The Current Landscape of Healthcare Collaboration in Nigeria

Months into his internship at a top Nigerian hospital, Aliu* was fed up. He had spent years training to become a medical laboratory scientist, but in just a few months of working, he felt his professional identity being questioned at every turn. He watched, often helplessly, as physicians interfered with his work—subtly questioning lab results, requesting re-runs without clear justification, and in many cases, having to revert to the Head of Department (a doctor) before any result could be deemed “authentic enough to release.”

At first, Aliu thought these practices were unique to his facility. But conversations with fellow interns in other hospitals quickly disabused him of that notion. Across the country, variations of the same experience were playing out: laboratory scientists working under the shadow of medical dominance, struggling for recognition, autonomy, and professional respect.

As an undergraduate, he had heard stories about the strained relationships between healthcare professionals—especially between laboratory scientists and doctors—but he assumed those accounts were exaggerated. After all, many of his close friends were medical students, and debates about professional roles had never escalated beyond casual banter.

So imagine Aliu’s surprise when he found the tension not only real, but deeply rooted—woven into the fabric of a system that talks about teamwork but rarely practices it.

Like Aliu, many laboratory scientists and indeed many other healthcare workers have stories for days where there has been a lack of cohesion or even blatant disregard for their services, actions built on the foundation of historical power dynamics and a general lack of trust. Although healthcare delivery involves a wide range of professionals—doctors, nurses, pharmacists, medical laboratory scientists, radiographers, physiotherapists, and more—they rarely function as a true team. Instead, institutional structures tend to reinforce hierarchy rather than cooperation.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the strained dynamic between doctors and laboratory scientists. In many facilities, doctors assert supervisory control over lab procedures, sometimes dismissing the scientist’s expertise outrightly, as exemplified in Aliu's story

Laboratory scientists, in turn, resist what they perceive as encroachment and undervaluation, leading to friction that directly affects the speed and quality of patient care.

These issues are symptoms of a system that was never intentionally designed for collaboration. Healthcare professionals are trained separately and often enter the workforce with little appreciation for the contributions of other arms. What should be collaborative becomes a battleground of roles, responsibilities, and recognition.

Why Utopia seems out of reach: Exploring Cultural and Systemic Barriers to a Cohesive Healthcare System

Historical hierarchies: Top at the list of reasons why disunity in the Nigerian healthcare delivery system prevails is the history that birthed current practices. One cannot fully understand the fractured relationships within Nigeria’s healthcare system today if there is no retrospection—a look back to how the system itself was built—and more importantly, who it was built around.

During the colonial era and the early years of Nigeria’s post-independence development, healthcare delivery was centered almost entirely around the physician. Doctors were trained both locally and abroad, often returning with prestigious credentials that elevated their social status.

They were positioned not just as clinical leaders but as the de facto administrators of healthcare services. As other health professions—nursing, pharmacy, and medical laboratory science—emerged, they were seen as auxiliary support, essential but secondary. This is what is known as the physician-centric model.

Unfortunately, this model became deeply embedded in policy, training, and institutional structures. Hospitals were—and often still are—governed by medical directors, most of whom are doctors. Curricula were developed individually, with minimal emphasis on interdisciplinary education. Even hospital workflow reinforced the hierarchy, placing doctors at the top of the decision-making ladder, while other professionals followed downstream.

The problem with this system of service delivery is that while it once was built to serve [and did serve] a few, it now hinders a healthcare team built to serve many.

As more health professions developed into independent disciplines with their own governing councils and regulatory frameworks, the desire for autonomy and recognition grew. But by then, the culture of hierarchy had calcified, making respect and collaboration a tough nut to crack. This legacy still shapes how healthcare workers interact today.

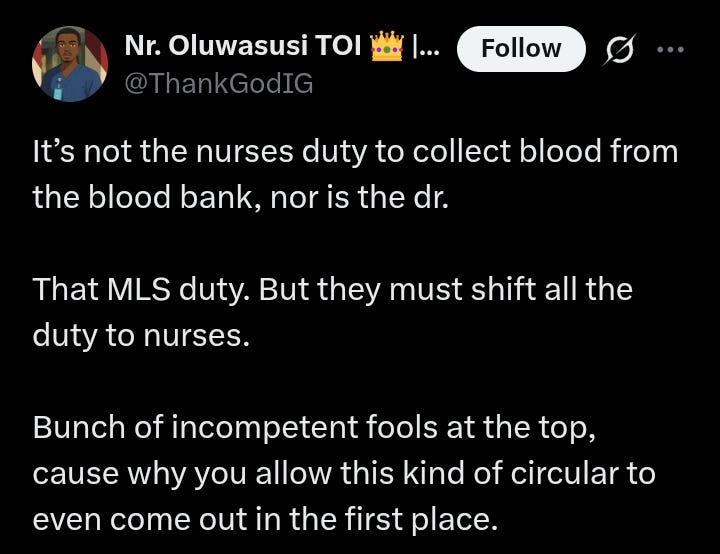

For many doctors, the habit of oversight and control is seen as natural—even necessary. For other professionals, this control is stifling and dismisses their expertise, as seen in this 2019 publication by The Punch. The result is a lingering tension that breaks out with the slightest provocation.

Professional territorialism: Beyond the issue of who's in charge, there are deeper issues of who controls what and who feels they should be in charge. These three concepts may look alike to the unassuming eye, but for healthcare professionals trying to gain and keep respect, the devil is in the details. With territorialism, it is about who holds the highest position, but deeper than that is the issue of who has the “right” to designate roles to other professionals.

Over the years, each healthcare profession in Nigeria has carved out its own space, often to the point of defensiveness. The result is a fragmented system where, instead of working together as a cohesive unit, professionals often operate as rival factions. This is exemplified in an article by Punch Healthwise in 2022, where we see the two doyens interviewed took different stances on the topic of result interpretation. This territorialism is most obvious in cases where job roles overlap.

When a laboratory scientist offers an interpretation of test results, doctors may challenge their conclusions, assuming that the clinical context should override the scientific one. Pharmacists, who are expected to offer drug-related counsel, often find their input sidelined by doctors who feel their treatment plans are final, as documented in this 2016 study.

This kind of mindset is particularly damaging in an already overstretched healthcare system like Nigeria's. It stifles the flow of information and wastes precious time that could be spent on addressing patients' needs.

Systemic Inefficiencies: The collaboration we struggle to achieve has also been linked to a lack of infrastructure for the healthcare system in Nigeria. This deficiency is reflected in the yearly budgetary allocation to the health sector. For the 2025 budget allocation, the health sector got ₦2.48 trillion, a higher amount than the 2024 allocation of 1.23 trillion. While this increase is noteworthy, it is a far cry from the agreed benchmark of 15% that the health sector should receive from the yearly budget.

With this kind of allocation to the health sector, it is little wonder that systemic inefficiencies exist. From outdated infrastructure to underfunded facilities, Nigeria’s healthcare system struggles with issues that directly hinder the smooth functioning of all its arms.

Hospitals often operate with limited resources, insufficient staff, and outdated equipment, which forces healthcare workers to cut corners and work around broken systems.

For instance, medical records are often kept manually, with studies reporting an adoption rate of 15%-23% for electronic health records. This compels professionals to spend excessive time searching for information, instead of focusing on what is truly important – the patient.

Even when all the players are available and ready to work, these structural inefficiencies—rooted in years of underinvestment and poor planning—drag down the healthcare system's potential. Teamwork becomes secondary to simply getting through the day, leading to a lack of coordination that only exacerbates the problem.

Beyond historical hierarchies, territorialism, and systemic inefficiencies, several other barriers continue to undermine synergy within Nigeria’s healthcare system, some of which include:

Lack of adequate policy frameworks

Unaddressed grievances and union tensions like the one existing between JOHESU and NMA.

Differences in language use and communication style.

Imagining Utopia: What Could Collaboration Truly Look Like?

Despite the challenges, there are glimpses—however faint—of what a functional, collaborative healthcare system in Nigeria could resemble. Utopia, in this sense, isn’t about removing hierarchy altogether. It's about redefining leadership as a shared responsibility—not a dictatorship.

It’s a model where mutual respect is the norm, not the exception.

A practical example of this kind of synergy exists within Nigeria’s Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) program. In many ART clinics across the country, healthcare workers all work in coordinated roles toward one goal: managing HIV effectively. Doctors lead clinical diagnosis and treatment initiation, but they rely on accurate lab testing by laboratory scientists, medication management by pharmacists, patient counselling by nurses and adherence coordinators, and data tracking by data managers. While not without its challenges, the ART program demonstrates what’s possible when roles are clearly defined and collaboration is built into the system. It may not be utopia, but it offers a rare, working glimpse.

Now imagine a healthcare system where this model isn’t the exception but the rule. One where medical students learn side-by-side with nursing, pharmacy, and laboratory science students, clinical protocols are developed with contributions from all relevant disciplines, and leadership isn’t static or monopolised but inclusive and rotational, welcoming professionals from diverse backgrounds to bring fresh perspectives into administrative and policy spaces.

Most importantly, in this version of the system, the patient truly becomes the center. Not as an abstract entity, but as the reason everyone is in the room.

The Path to Utopia: Steps Toward a Collaborative Healthcare System

Is this ideal healthcare delivery system possible in Nigeria? Yes. No. Maybe. Depending on who you ask, you will get variations of these responses.

Here is what a supervising chief thinks of the topic:

I do think that a day will come when the synergy we now dream of will become a reality. But, it's not happening now or even in the near future. We've yet to have real conversations on it, and even when we're having these conversations, we're not putting actions to our words yet. I'm talking about setting up structures that will sustain it. So, yes, I believe that kind of Nigeria will exist, just not now.”

Hope. This is what keeps many health professionals going on days when another heated argument crops up between nurses and doctors, doctors and laboratory scientists, or nurses and laboratory scientists.

The hope that one day, it will get better. However, our one-day may never come if we (health professionals) are not willing to take the bull by the horns and be proactive. Being proactive is not playing the blame game; rather, it's taking serious, active steps towards ensuring that the utopia we dream of will no longer be a distant possibility. In a recent episode of Labcast, a podcast by MedLabConvo, health professionals from different fields came together to discuss what exactly we should be doing right. But since we're having this discussion here, we might as well outline some necessary steps that can be taken to get closer to this ultimate dream

For starters, the education system should be addressed. Receiving lectures in isolation, especially from the “professional” courses phase, most often plays into the divide at the healthcare delivery level. Universities and teaching hospitals must intentionally introduce interdisciplinary coursework, joint seminars, and collaborative projects. Working together on seminars and projects in what can be considered Interprofessional Education (IPE) will help students understand and respect what each does in their respective fields.

Next, there should be policy reforms and clear role definitions. The Ministry of Health and relevant regulatory bodies must clarify the scopes of practice across professions—removing overlaps that breed conflict.

Additionally, leadership positions in healthcare institutions should not be exclusive to doctors. Hospital administration and key decision-making roles should include other fields—laboratory scientists, pharmacists, nurses, and health administrators—on equal footing.

Some issues cut across various fields in the healthcare system, like antimicrobial resistance and patient care and safety. Forming unified professional bodies that cut across the different fields, coming together to address some of these issues, ensure not only the ultimate goal of adequate healthcare delivery but also ensures there is interprofessional collaboration. The One Health approach to healthcare delivery, backed by the World Health Organisation, provides a blueprint for an organogram and functions that health institutions can adopt.

Comments

Utopia, in the context of Nigeria’s healthcare system, may seem like wishful thinking, but the cracks we see today are not beyond repair. Real progress begins with acknowledging that no single field holds all the answers in patient care. A truly functional system thrives on respect, collaboration, and the recognition that each professional brings a piece of the puzzle.

Recommendations

To move forward, we must invest in interprofessional education, create policies that foster cooperation rather than competition, and build leadership models that are inclusive and balanced. The journey to utopia isn’t paved with perfection, but with deliberate reforms and a collective commitment to doing better—for the system, and most importantly, for the patient.

The most brilliant piece I've read this week!

Wow

So inspiring and educating