Aim

This article aims to explore the current global vaccination hesitancy crisis, emphasizing how the lack of visible consequences from life without vaccination contributes to this trend and; examine other factors influencing public perception and acceptance of vaccines.

Keywords

Vaccination, hesitancy, public health, misinformation, WHO, education.

Method

An expository essay.

Principle

From variolation to what we now call vaccination, humans historically have always sought out ways to protect themselves against deadly diseases. Since Edward Jenner's discovery in 1796 that a previous exposure to cowpox inferred immunity against infection with smallpox, there have been several attempts and successes at protecting humans against futuristic, probably fatalistic infections.

Undoubtedly, vaccination has been a cornerstone of public health, preventing the spread of infectious diseases. However, in recent years, a growing trend of vaccine hesitancy has emerged globally.

This hesitancy is partly due to the absence of visible consequences from vaccine-preventable diseases, leading to complacency among different populations. Understanding the reasons behind vaccine hesitancy—including safety concerns, misinformation, religious and cultural influences, and psychological factors—is crucial if this public health challenge is to be addressed properly.

Procedure

The Concept of “Seeing is Believing”

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines vaccine hesitancy as a delay in acceptance or refusal of safe vaccines despite the availability of vaccination services, and in 2019, it was declared as one of the ten global threats to public health. The trend of refusal of vaccines has increased over the years, and there are so many factors influencing this increasing trend.

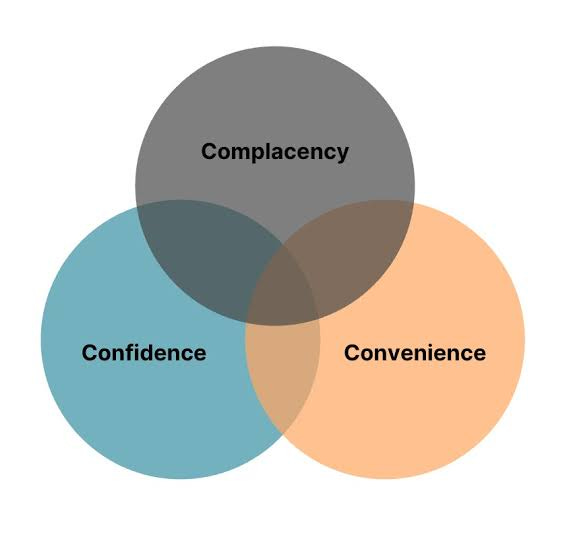

They have been broadly categorized by the WHO into three (3):

Convenience, which answers the question: How convenient is getting this vaccine? And explores the affordability and nearness of vaccination centers to individuals;

Confidence, which addresses trust in vaccines and the vaccination process as well as the health system responsible for its administration; and

Complacency, which describes the absence of desire to get vaccines based on several reasons that could be group-influenced or personal.

However, of these three categories, complacency due to the increasing lack of visible outbreaks stands out as a major factor.

When diseases that vaccines can prevent become rare or nonexistent in a community, there may be less urgency to vaccinate, and this complacency is deeply rooted in the belief that a lack of outbreak indicates that the storm is over, creating a false sense of security and a decline in the number of populations seeking vaccination.

Using the instance of the English community, who over the years have not witnessed any real-life case of measles, given that the disease had since been eliminated from the country, there has been a decline in vaccination rates, which unfortunately has led to new sporadic outbreaks across several regions.

These outbreaks serve as stark reminders that without high vaccination coverage—typically around 95% for herd immunity—diseases can make a comeback even in populations that have not experienced them in years.

This case-instance not only appeals for measles but for other diseases that have long been eradicated or whose incidence has greatly reduced due to past effective vaccination campaigns like polio and smallpox.

So long as populations do not “see” the disastrous effects of these diseases against which vaccines are administered, there will be a perpetual state of “unbelief” in the usefulness of vaccines.

Other Factors Contributing to Vaccine Hesitancy

Although complacency due to a lack of visible outbreaks stands as a major reason for vaccine hesitancy in certain regions of the world, there are other factors that hugely contribute to this phenomenon in other regions.

As earlier mentioned, WHO categorizes the many factors that contribute to vaccine hesitancy into 3 based on:

convenience

complacency, and

confidence.

However, the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) categorizes these factors into:

Contextual influences

Individual and group influences

Vaccine and vaccination-specific issues.

This article will explore these factors under this categorization by ECDC.

Contextual Influences

Contextual influences are historic, social, cultural, environmental, economic, political, and institutional factors that make people hesitant towards taking vaccines. The most popular example of contextual influence is conspiracy theories.

Good old instances of conspiracy theories surrounding vaccines are that vaccines are produced to serve the economic or political interests of big pharmaceutical companies, governments, or Western countries.

There are also beliefs that vaccines are implemented as a strategy to reduce world population, that humans are already okay as they are, therefore vaccines are entirely unimportant, and also those of a religious bent who opine that taking vaccines shows distrust of God’s decision on how we were created.

Individual and Group Influences

These include personal perceptions about vaccines and influences from one’s social environment. One very common instance is the belief that vaccines can cause severe diseases and side effects, that their long-term effects are unknown and may contain dangerous compounds that in the future may be triggered to cause harm to the individual.

A good instance of group influence is the Amish community, which believes that vaccines are more detrimental to human living and survival than they are ever good, claiming that vaccines are prime causes of genetic mutations that have led to an increase in neurologic and behavioral conditions such as schizophrenia and autism.

Another important example is what played out during the COVID-19 outbreak, where some of the immediate side effects of the vaccine were magnified so much that they generated public outcry, fear, and outright rejection of the vaccine in many countries.

Additionally, mistrust of health professionals and the health system as a whole, a fear that vaccines may pose more risk to children on the assumption that their bodies are not strong enough to fight the effects of vaccines, and societal norms and pressure from family and friends all influence vaccine hesitancy.

Anti-vaccine Activism

This is defined as a total opposition to vaccination. Anti-vaccinationists have in more recent years been known as anti-vaxxers. Anti-vaxxers’ agendas have been found to change over time, sometimes the reasons being more connected to political and economic goals, while other times it is either religious or personal.

For some people who are skeptical about vaccine use, they consider the name "anti-vaxxer" a slur, most often preferring to be known as “vaccine-risk-aware” folks.

One of Hollywood’s most popular anti-vaxxers is Jenny McCarthy.

While Jenny identifies as a pro-safe-vaccine crier, her stance on vaccines, especially since attributing her son’s autism diagnosis to the MMR vaccine he received when he was younger, has placed her on the long list of popular anti-vaxxers.

Find her story and similar stories

Vaccine and Vaccination-specific Issues

These include various issues that are related to vaccines and their administration. It could be lack of access to vaccination centers, fear of the consequences of new untried vaccines, or, at certain times, the financial cost of getting some vaccines.

Case Studies of Vaccine Hesitancy

Vaccine hesitancy is complex and context-specific, varying across place, type of vaccine, and time. In places like the United States, hesitancy differs between social classes, with communities of color being most hesitant about vaccines. For the elite, it is more often a mistrust of the government or personal experiences.

In places like Nigeria, social class, education level, and religious beliefs play a frontline role in contributing to this growing trend. Behaviors like parents double-checking before their wards are vaccinated either by asking their neighbors with children of the same age, reaching out to more informed people, or, in some instances, putting a call across to a familiar health provider to confirm if their children should receive such vaccinations also indicate a deep-seated fear or distrust for the safety of the vaccine, the health system, or the capacity of the health provider to act correctly.

How do we fight this trend?

Vaccine hesitancy is multifaceted; hence, tackling it has to be dynamic and tailored to the local context.

Answering questions like “why are people skeptical about vaccines?" and “why is there a reduction in the number of people taking this vaccine?" will help create solutions that will address the problem locally. Depending on the factors influencing hesitancy in a region, some strategies that have been tried and true include, but are not limited to:

Clear and transparent communication: Nothing builds trust more than transparency. When people understand clearly and fully the advantages and possible disadvantages of a vaccine, it helps them make informed decisions about vaccines. Murky information only breeds the notion that there are ulterior motives

Involving community vaccine champions: training community leaders, healthcare providers, and trusted figures to act as vaccine advocates can address hesitancy.

Comments

Vaccination hesitancy is real, and if we are going to see a decline in this trend, then understanding the factors at play is key. By identifying these different factors in different communities, policymakers and governments can work together towards developing effective strategies to improve vaccine uptake.

Recommendations

We would recommend actions and policies targeted at enhancing community engagement efforts, providing clear educational resources, and fostering trust through transparent communication. Ultimately, overcoming vaccine hesitancy is essential for safeguarding public health and preventing future outbreaks of preventable diseases.